Research

DNA and histones are arranged in the nucleus in a highly condensed structure known as chromatin. Cellular processes that unwind the double helix—such as transcription, replication and DNA repair— have to overcome this natural barrier to DNA accessibility.

Multicellular organisms also need to control their use of cellular energy stores. Nutrient metabolism plays a crucial role in organismal homeostasis, influencing energy consumption, cell proliferation, stress resistance and lifespan. Defective glucose utilization causes numerous diseases ranging from diabetes to an increased tendency to develop tumors. In order to respond appropriately to changes in energy status, cells need a finely tuned system to modulate chromatin dynamics and to respond to metabolic cues. Reciprocally, chromatin changes necessary for cellular functions need to be coupled to metabolic adaptations.

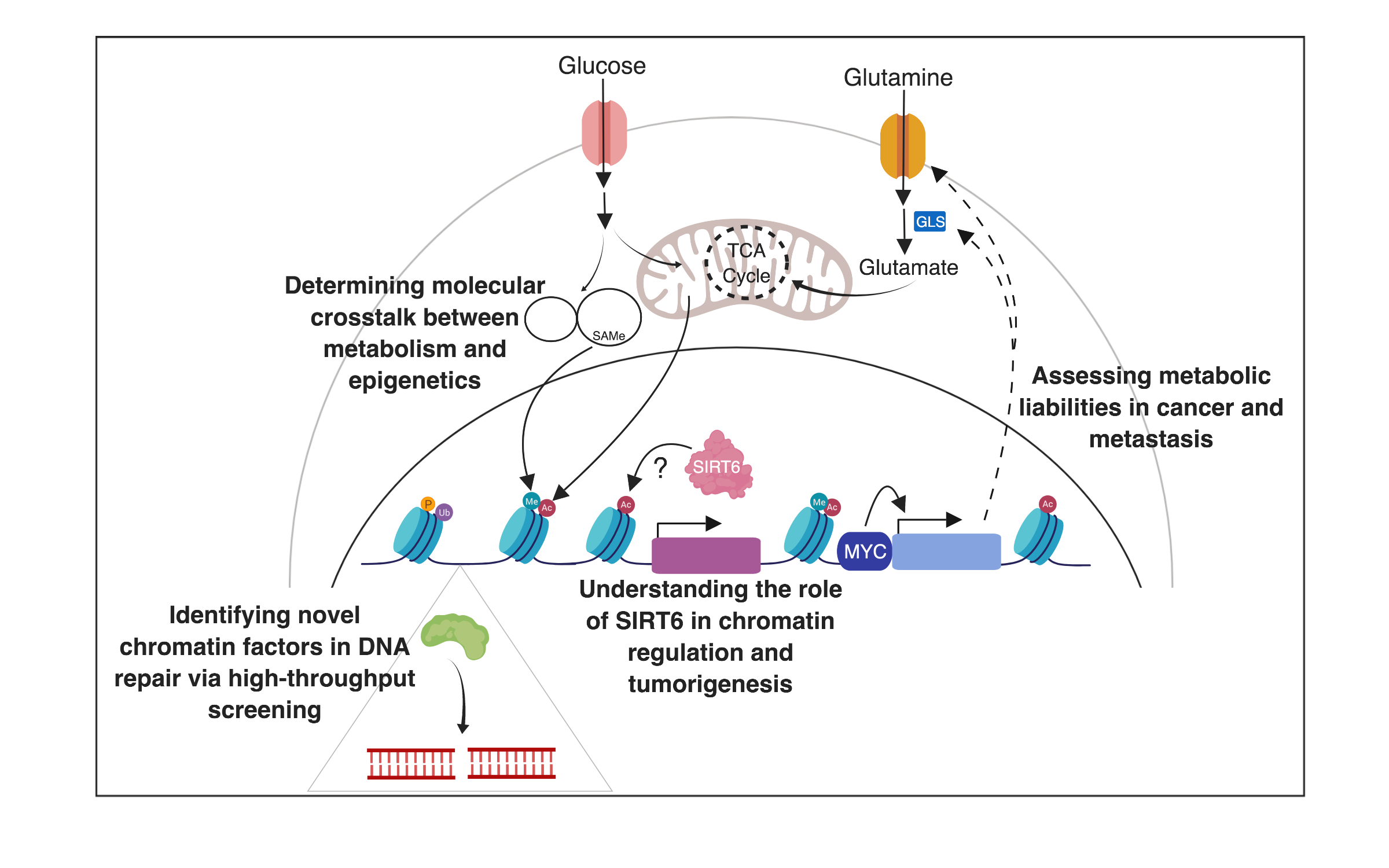

Our lab is interested in understanding the influence of chromatin on nuclear processes (gene transcription, DNA recombination, and DNA repair) and the relationship between chromatin dynamics and the metabolic adaptation of cells. One of our interests is studying a group of proteins called SIRTs, the mammalian homologues of the yeast Sir2. In particular, our work has focused on the mammalian Sir2 homologue, SIRT6. In past years, we identified SIRT6 as a key modulator of metabolism, functioning as a histone H3K9 deacetylase to silence glycolytic genes; thus directing pyruvate to the TCA cycle to promote ATP synthesis. This function appears critical for glucose homeostasis, as SIRT6 deficient animals die early in life from hypoglycemia. Remarkably, we found SIRT6 to act as a tumor suppressor in multiple cancers by inhibiting aerobic glycolysis, a process described by biochemist and Nobel laureate Otto Warburg decades ago (i.e., the Warburg effect), yet the molecular mechanisms behind this metabolic switch remained a mystery. We found that SIRT6 is a critical epigenetic modulator of the Warburg effect, providing a long-sought molecular explanation to this phenomenon. Importantly, new work from the lab suggests that tumors exhibit metabolic heterogeneity, and current work from the lab aims to understand whether such heterogeneity is dynamic, and whether it influences chromatin changes in cancer cells, as a mechanism to acquire “epigenetic plasticity”. In recent years, we have broadened our research to explore roles of one carbon metabolism (1C) in chromatin dynamics, particularly how the universal donor SAM is modulated in cells, exploring novel metabolic liabilities in cancer, new chromatin modifications, and new chromatin modulators of DNA repair. Importantly, past work on metabolism and chromatin in cancer has focused on primary tumors. We are now exploring the unique metabolic and epigenetic adaptation of metastatic cells, something that remains mostly unknown. In recent studies we have uncovered novel genes that are upregulated in metastatic cells, driving the survival of disseminated tumor cells in the new niche. These genes include metabolic enzymes and transporters, suggesting that metabolic adaptations will be key for metastatic cells to outgrowth, and we are currently exploring whether metabolic heterogeneity is a feature of metastasis as well. We use a number of experimental systems, including biochemical and biological approaches, unique reporters of metabolic pathways as well as genetically engineered mouse models and analysis of human patient samples.

Specific projects:

1. Determining the role of SIRT6 in tumorigenesis and aging

2. Identifying novel histone modifications, and their roles in DNA repair

3. Determining molecular crosstalk between epigenetics and metabolism

4. Discovering non-genetic (epigenetic and metabolic) drivers of metastases